Download PowerPoint versions of figure.

Inside Collection (Textbook): American Health Economy Illustrated

11.1 Rising Health Costs Hindered Growth in American Workers' Earnings

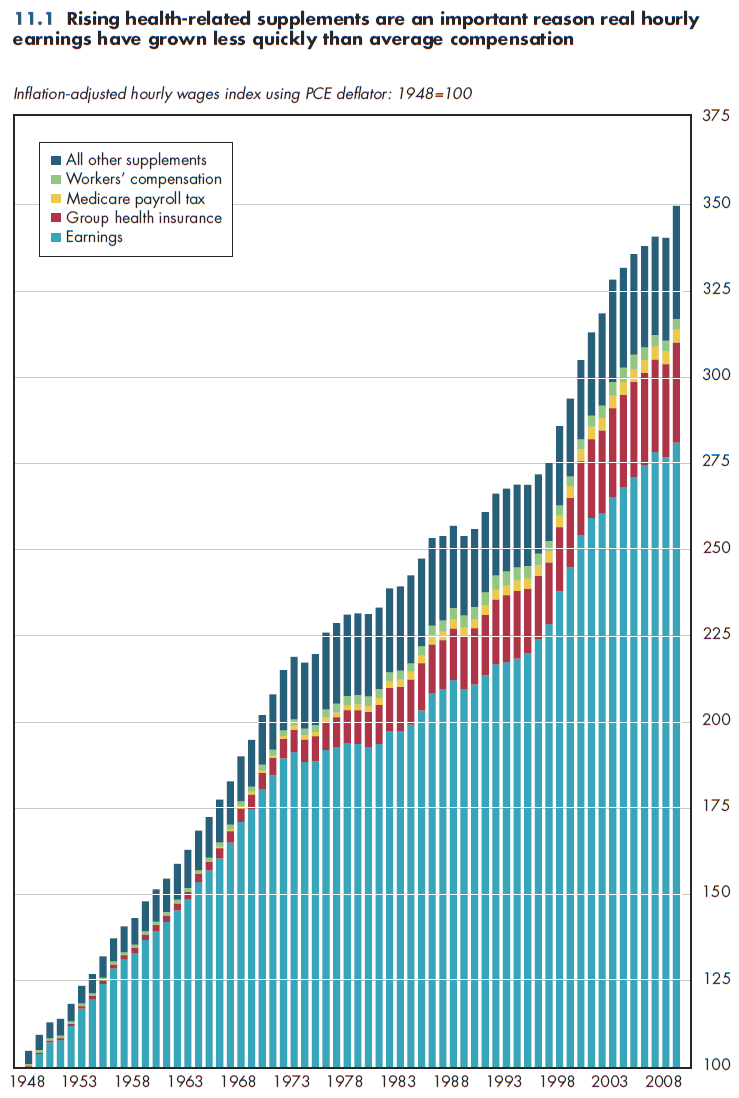

Summary: For the average American worker, growth in real hourly earnings has in recent decades lagged behind growth in real compensation per hour, due in part to rising health costs.

Inflation-adjusted hourly wages in 2008 were 2.8 times as high as they were 60 years earlier. This has occurred despite rapid growth in supplements to wages and salaries, including employer-provided health coverage, payroll tax deductions for health-related purposes such as Medicare and workers' compensation, and other fringe benefits.

The data in figure 11.1 include only the employer's contribution toward health insurance and social insurance. Thus, the 1.45 percent employer contribution for Medicare is included but not the parallel contribution made by the employee that appears as a deduction on most employee paychecks. Likewise, the "hidden" employer contribution to employer-sponsored health insurance is included, but not the employee share of the premium (which again shows as a paycheck deduction that reduces the monetary compensation that otherwise would go to the employee).

This calculation uses the PCE price deflator to remove the effect of inflation. For several reasons, the PCE price deflator is superior to the more commonly reported CPI. It more accurately reflects changes in the purchasing power of U.S. workers. Figure 11.1 is indexed to hourly earnings rather than total compensation. Thus, it also shows how much cash earnings would have increased had there been no increase in wage and salary supplements over the past 60 years. In that case, earnings would have been 3.5 times as high.

The exact percentages are not important. As an approximation, almost half the increase in compensation for wage and salary supplements was health-related. The lion's share of these health-related add-ons was for group health coverage. Because Medicare payroll taxes support the care of today's Medicare beneficiaries, some might question whether this is an employee "benefit" at all. However, from a social contract point of view, it does not matter whether individuals are literally banking for their own future retiree health expenses or merely making their contributions into a pool in exchange for a promise to receive such benefits in the future. The purpose is unquestionably health-related.

Downloads

References

- Department of Commerce. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Collection Navigation

- « Previous module in collection 10.6 Increased Longevity and Shorter Working Life Have Lengthened the Period of Retirement for Males

- Collection home: American Health Economy Illustrated

- Next module in collection » 11.2 Employee Compensation in Health Services Is Slightly Higher than All Workers Average

Content actions

Give feedback:

Download:

Add:

Reuse / Edit:

Twin Cities Campus:

- © 2012 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved.

- The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer. Privacy

- Last modified on Sep 26, 2013 2:07 pm -0500