Download PowerPoint versions of both figures.

Inside Collection (Textbook): American Health Economy Illustrated

13.3 Lower-Income People Have Worse Health

Summary: Health status generally is worse among those who have lower incomes; poverty status explains only some of the health status differences related to race.

It has long been known that the poor generally are in worse health than is the rest of the population. Numerous methods can measure health status. Although not perfect, self-reported health status is a surprisingly good measure. Careful studies show that self-reported health status does a good job of predicting future mortality. That is, those who report their health status as "poor" are far more likely to die within the next year than are those who view their health as "good" or "excellent."

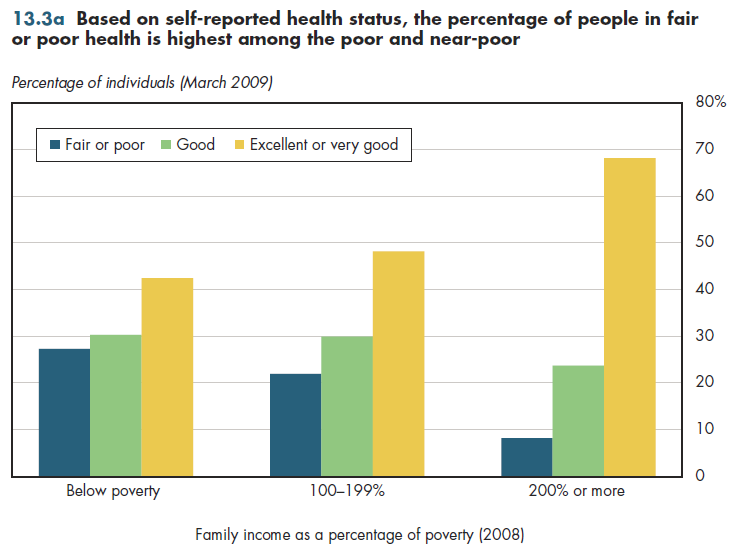

Using this measure, only approximately 40 percent of the poor say that their health is excellent compared with almost half of the near-poor and almost seven in 10 of those who have incomes above 200 percent of poverty. Conversely, more than 25 percent of the poor are in fair or poor health compared with fewer than 10 percent of those above 200 percent of poverty (figure 13.3a).

This relationship works in both directions. Some people are poor because of poor health. Poor health might prevent them from working or lower the amount that they can earn. Poverty itself can contribute to poor health. Those who live in poverty are more likely to be concentrated in areas that have higher crime rates, for example, putting them at risk of a violent injury that might permanently compromise their health for the rest of their lives. Likewise, poor people are more likely to drive less expensive, lighter cars that put them at higher risk of an auto-related injury. For many reasons too complicated to explain here (and too poorly understood), smoking rates and obesity also tend to be higher among those who have the lowest incomes.

Those who have the greatest general, objective need for health services also are least able to pay for such care. Consequently, how to finance such care is a social problem faced by all nations.

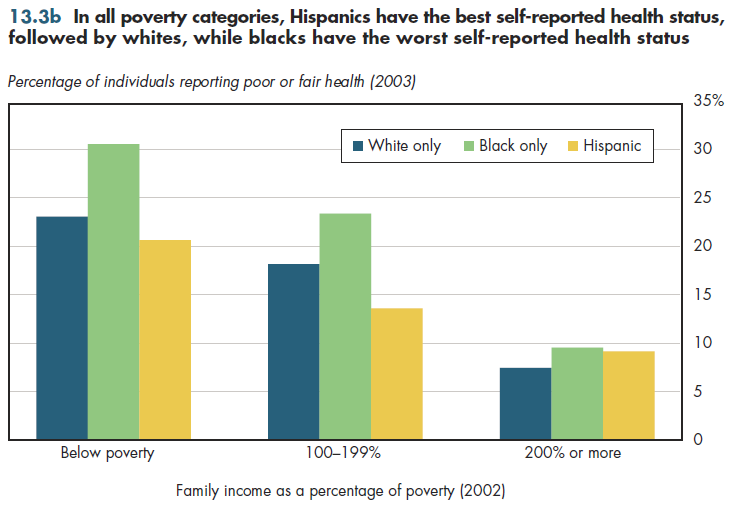

Socioeconomic factors explain only some of the persistent health differences across racial and ethnic groups. Even after accounting for higher poverty rates among blacks and Hispanics relative to whites, health status differences remain among these groups (figure 13.3b). The degree of these disparities grows smaller as incomes rise. Thus, economic growth and rising incomes will help naturally dissipate many disparities. However, they cannot be expected to disappear entirely even if incomes were equalized.

Downloads

References

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Collection Navigation

- « Previous module in collection 13.2 Government Insurance Covers Half of the Poor

- Collection home: American Health Economy Illustrated

- Next module in collection » 13.4 Poor Children Are Much Less Likely to Have Private Health Coverage than General Population

Content actions

Give feedback:

Download:

Add:

Reuse / Edit:

Twin Cities Campus:

- © 2012 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved.

- The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer. Privacy

- Last modified on Sep 26, 2013 1:37 pm -0500