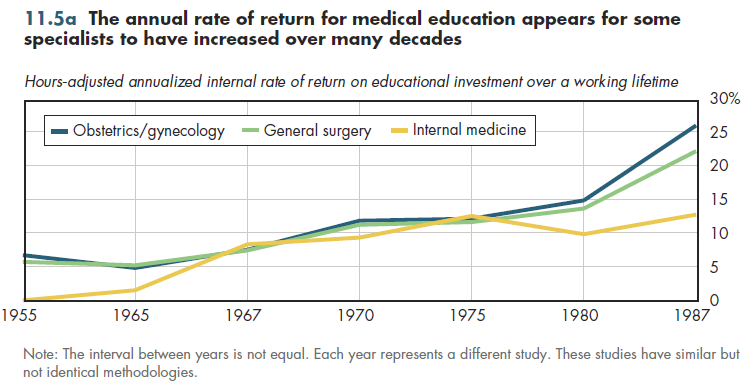

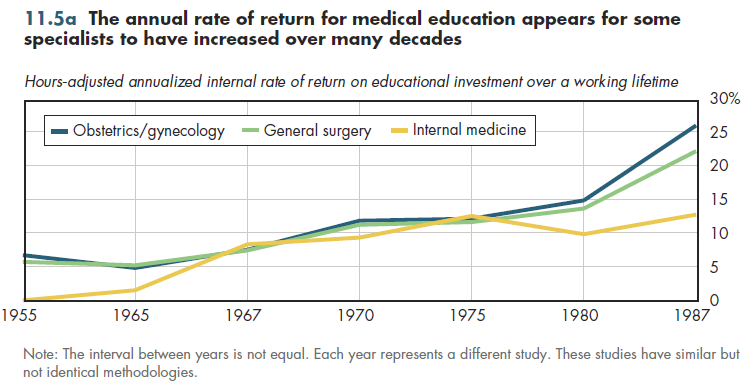

The annual rate of return to investment in physician education currently is at double- digit levels. Approximately 50 years ago, earlier studies found that such rates of return were much less than 10 percent (figure 11.5a). The numbers represent the hours-adjusted annualized rate of return on medical education over a doctor's working lifetime. The investment in medical education includes direct costs (tuition, books, and so forth) and indirect costs, that is, the income foregone by attending school/ residency rather than working.

The return on this investment is the higher annual compensation physicians receive relative to what similar individuals receive on average during each year of their career. The hourly adjustment is important because physicians work longer hours than the average worker does. The rate of return is annualized to make it the same as other investments. For example, from 1900-2009, the total rate of return for the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) was 9.4 percent.

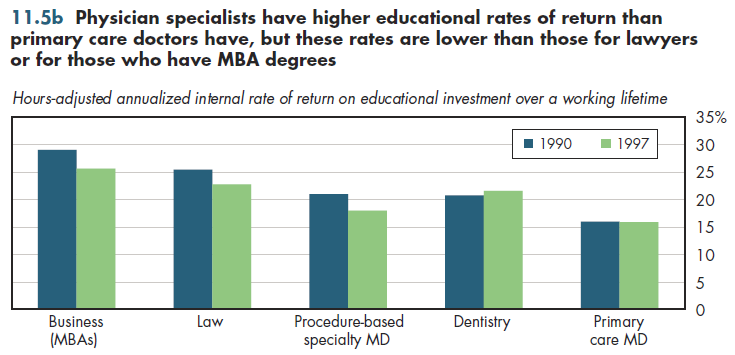

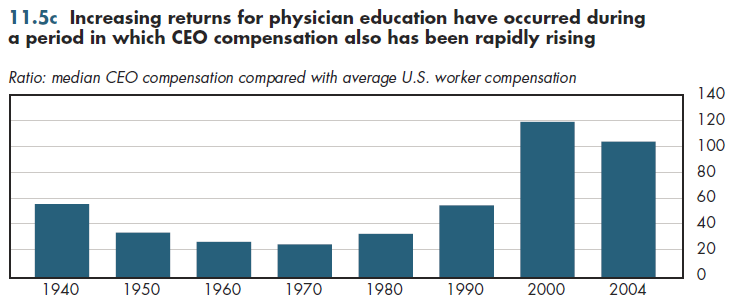

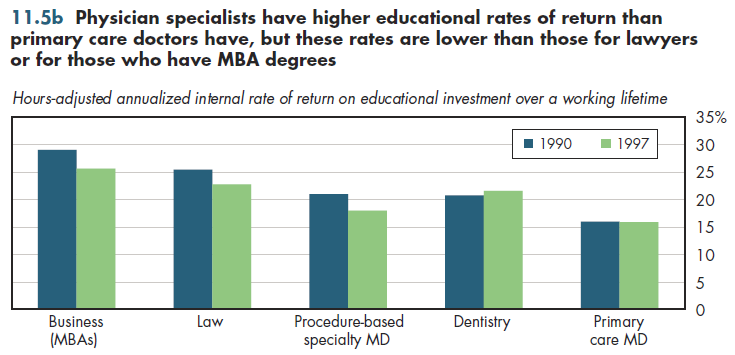

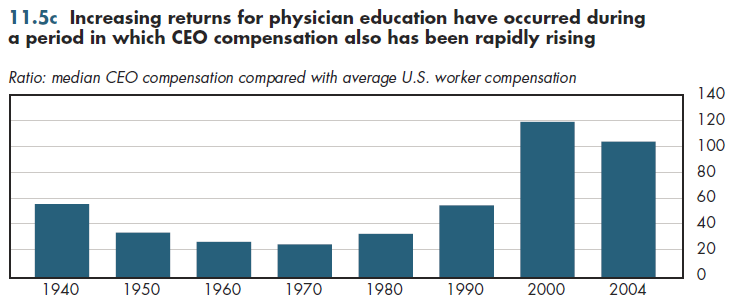

These data are approximations because such information for every category of physician is not available. Each of the studies that constitute the data displayed in figure 1.5b differs in its methodological details. However, they suggest that a typical physician earns a healthy rate of return compared with investing comparable resources in the stock market. These sizable rates of return appear somewhat less than for other professional degrees such as MBA or law degrees (figure 11.5b). Dentists and physician specialists have comparable rates of return, but primary care doctors have lower—albeit still impressive—rates of return. This is consistent with the general impression that primary care doctors are "underpaid" relative to specialists. The study shown defined procedure-based medicine as surgery, obstetrics, radiology, anesthesiology, and medical subspecialties. Trends for these other professions are not available, but CEO compensation has increased considerably, relative to that of average workers (figure 11.5c).

These comparisons suggest that high prices for health labor in the United States might simply reflect higher returns to skilled labor across the board. If doctors were paid much less, more people might get MBAs or law degrees instead. This might reduce health spending, but reasonable people might disagree on whether it would improve social welfare.

Download PowerPoint versions of all figures.

- New York Times. The Wide Divide. April 6, 2006. http://www.nytimes.com/

imagepages/2006/04/09/business/businessspecial/20060409_PAY_GRAPHIC. html?ref=executivepay (accessed November 12, 2010).

- Phelps CE. Health Economics. HarperCollins Publishers. 1992.

- Weeks WB, AE Wallace, MM Wallace and HG Welch. A Comparison of the Educational Costs and Incomes of Physicians and Other Professionals. New England Journal of Medicine 1994; 330(18):1280-86.

- Weeks WB and AE Wallace. The More Things Change: Revisiting a Comparison of Educational Costs and Incomes of Physicians and Other Professionals. Academic Medicine 2002; 77(4):312-19.