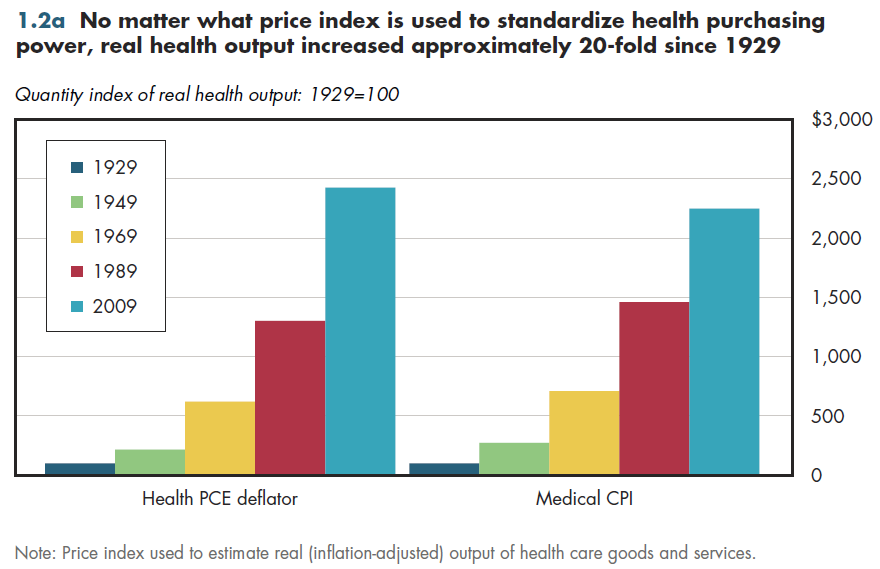

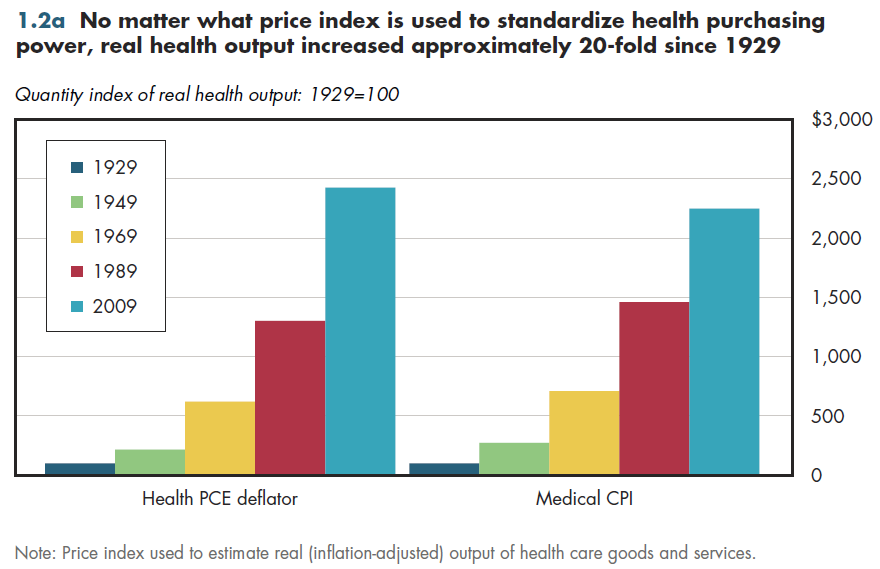

Adjusting medical care prices in several ways, inflation-adjusted health care output rose at least 20-fold over the past 80 years. Estimates of NHE output cannot be precise; thus, estimates of changes over decades are unavoidable approximations. NHE includes many different goods and services. No adequate way exists to convert them to a common unit of output to measure a combined total. Therefore, adding all health care goods and services in proportion to their relative prices is customary.

For decades, medical price inflation usually has outpaced general inflation. To gauge how much the quantity of NHE has grown exclusive of medical price changes, NHE must be deflated by a measure of price inflation specific to medical care. Because relative prices change over time (for example, the hourly rate of physician pay versus that of licensed practical nurses [LPNs]), the measured size of the health sector depends on the year of the prices used.

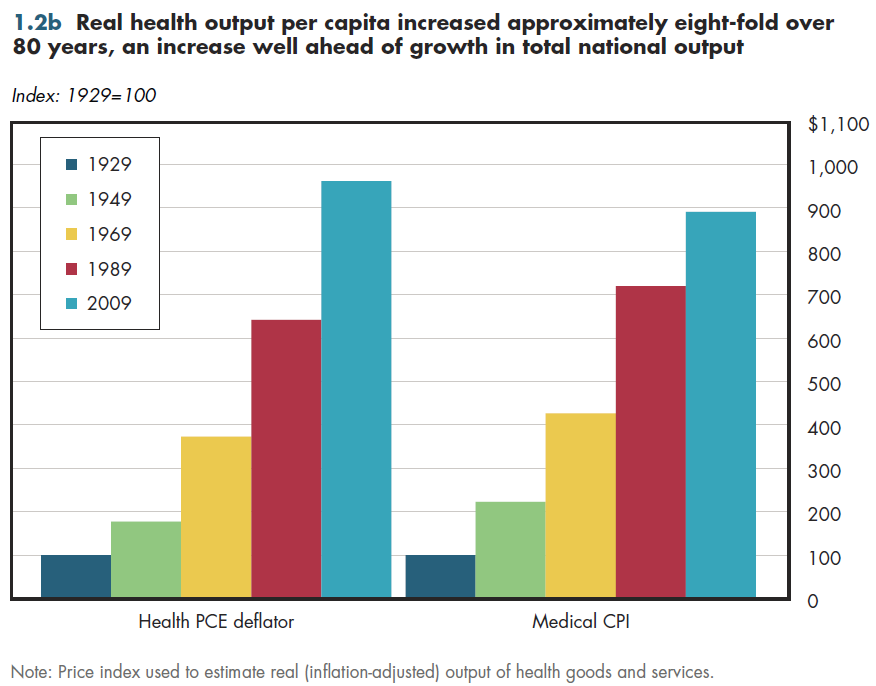

Both the health care deflator for personal consumption expenditures (PCE) and the CPI for medical care have limitations.

The PCE health care deflator counts all household medical care use regardless of how it is financed.

Therefore, it is a more complete measure of price changes across the entire medical market. The medical CPI is intended to reflect household out-of-pocket prices. Consequently, it places a smaller weight on expensive services disproportionately paid by insurance, such as hospital care.

Either index shows that real health output is at least 20 times as large as it was in 1929 (figure 1.2a).

NHE generally includes only output that is bought or sold in markets (including hospital and doctor care, even if these are provided "free" to the patient). It understates total output by excluding informal care provided by family or friends despite its importance for long-term care patients.

Good data do not exist for every item included in the NHE.

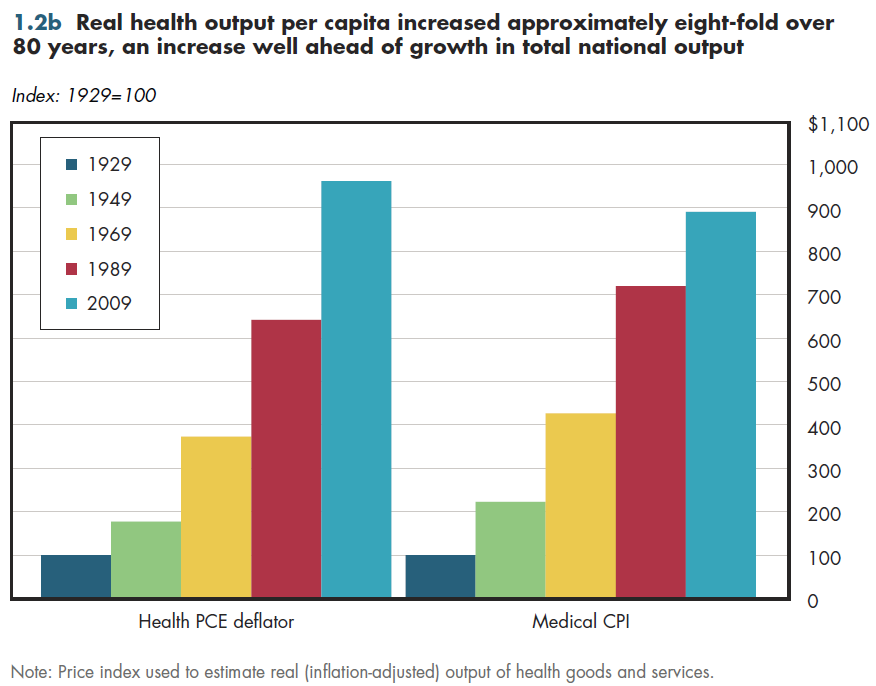

Real health output per person rose at least eight-fold in this period (figure 1.2b)— an amount much more comparable to the quintupling of real economic output per resident shown in figure 1.1b. There is little question that this increase in health output per capita has contributed to better health and longevity. However, which of these health gains has been worth its cost is a matter of considerable debate.

Download Excel tables used to create both figures:

Figures 1.2a/1.2b Tables.

Figures 1.2a and 1.2b both were created from the following table (the workbook includes all supporting tables used to create this table):

- Table 1.1 | U.S. Total Real National Health Expenditures Using Alternative Price Deflators: 1929 to 2021

Download PowerPoint versions of both figures.

Note that the downloadable Excel tables contain a detailed description of methods and sources; the extensive references are not replicated here. Below are references cited in footnotes for this module.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). 2013. Using Appropriate Price Indices for Analyses of Health Care Expenditures or Income Across Multiple Years. Last updated March 2013. Available at: http://meps.ahrq.gov/about_meps/Price_Index.shtml (accessed April 23, 2013).

- Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). 2013a. NIPA Tables Help. Available at: http://www.bea.gov/national/nipaweb/NIPAHelp.htm (accessed September 3, 2013).

- BEA. 2013b. Table 1.1.9. Implicit Price Deflators for Gross Domestic Product. Last revised July 31, 2013. Available at: http://www.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm (accessed August 10, 2013).

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2013. Consumer Price Index - All Urban Consumers (base period 1982-1984=100; not seasonally adjusted). Available at: http://www.bls.gov/data/#prices (accessed April 23, 2013).

- Feinberg, Lynn, Susan C. Reinhard, Ari Houser, and Rita Choula. 2011. Valuing the Invaluable: 2011 Update. The Growing Contributions and Costs of Family Caregiving. Washington, D.C.: AARP Public Policy Institute. July 2011. Available at: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/i51-caregiving.pdf (accessed September 3, 2013).